The moment a surgeon stands over a patient to close an incision, a critical decision happens in a split second. It is not just about closing a gap; it is about selecting the perfect tool to ensure the body heals correctly. While the terms are often tossed around loosely in conversation, for medical professionals and procurement managers, the distinction is vital. We are talking about the surgical suture. This tiny strand of material is the unsung hero of the operating room. Whether it is a deep abdominal surgery or a small cosmetic fix on the face, the suture holds the key to recovery. Understanding the type of suture, the suture material, and whether to use an absorbable or non-absorbable option is essential for successful wound closure.

What is the Real Difference Between a Suture and a Stitch?

It is common to hear patients ask, "How many stitches did I get?" However, in the medical world, accuracy is everything. There is a distinct difference between a suture and a stitch. The suture is the actual physical material used—the thread itself. It is the medical device used to repair the injury. On the other hand, the stitch is the technique or the specific loop made by the surgeon to hold the tissue together.

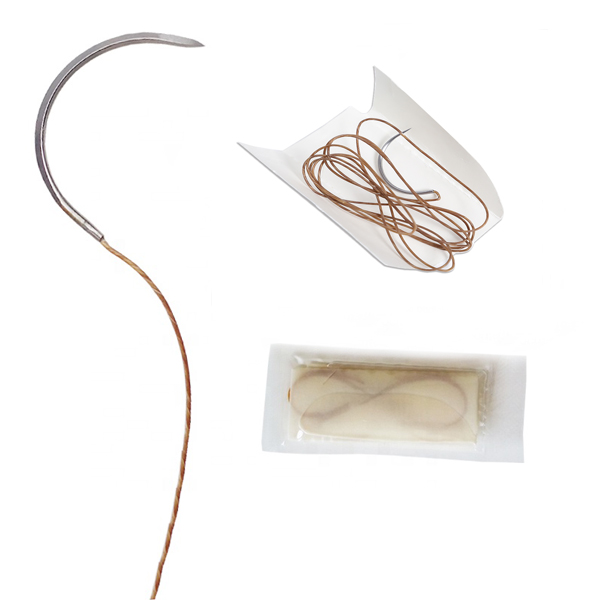

Think of it like sewing. The suture is the thread and needle, while the stitch is the loop you see on the fabric. A surgeon uses a suture to create a stitch. When a hospital orders supplies, they are buying sutures, not stitches. Understanding this terminology helps in selecting the correct suture material for the specific surgical site. Whether the goal is to remove stitches later or let them dissolve, the process always begins with the high-quality suture itself.

Analyzing the Structure: Monofilament vs. Braided Suture

When you look closely at a suture, you will notice its construction varies. This is not accidental; the structure dictates how the suture handles and interacts with tissue. A monofilament suture is made of a single strand of material. Examples include nylon, polypropylene, and polydioxanone (PDS). The main advantage of a monofilament structure is that it is smooth. It passes through tissue with very little drag, which reduces tissue reaction and trauma. Because it is a single smooth strand, it has no crevices to harbor bacteria, significantly lowering the risk of infection.

In contrast, a braided suture (or multifilament sutures) is composed of several small strands braided together, like a tiny rope. Silk suture and Vicryl are common examples. The braid makes the suture much more flexible and easy to handle for the surgeon. It creates excellent friction, which means it has good knot security—the knot stays tied tight. However, the braid can act like a wick, potentially drawing fluids and bacteria into the wound, which is why monofilament is often preferred for contaminated wounds. The choice between monofilament and a braided suture often comes down to a trade-off between handling ease and infection risk.

The Great Divide: Absorbable vs. Non-Absorbable Sutures

Perhaps the most significant classification in suture types is whether the body will break it down. Absorbable sutures are designed to break down within the body over time. They are primarily used internally for soft tissue repair where you cannot go back in to remove them. Materials like catgut (a natural material) or synthetic poliglecaprone and polydioxanone are engineered to degrade via hydrolysis or enzymatic digestion. These are what patients often call dissolvable stitches.

Conversely, non-absorbable sutures remain in the body permanently or until they are physically removed. Nylon, polypropylene, and silk suture fall into this category. Non-absorbable sutures are typically used for skin closure where the suture can be removed once the wound heals, or for internal tissues that need long-term support, such as in cardiovascular surgery or tendon repair. The suture acts as a permanent support structure. Choosing between absorbable and non-absorbable sutures depends entirely on the location of the wound and how long the tissue needs support to regain its strength.

Deep Dive into Natural and Synthetic Suture Materials

The history of the suture is fascinating, evolving from natural fibers to advanced polymers. Sutures are made from either natural and synthetic sources. Natural suture material includes silk, linen, and catgut (derived from the submucosa of sheep or beef intestine, rich in collagen). While catgut was the standard for centuries, natural materials often provoke a higher tissue reaction because the body recognizes them as foreign proteins.

Today, synthetic materials are widely preferred. Synthetic sutures, such as nylon, polyester, and polypropylene sutures, are engineered for predictability. They cause minimal tissue reaction and have consistent absorption rates or permanent strength. Synthetic options like poliglecaprone offer high initial tensile strength and pass through tissue easily. While a surgeon might still use silk suture for its superb handling and knot security, the trend in modern medicine is heavily leaning toward synthetic options to ensure the suture performs exactly as expected without causing unnecessary inflammation or tissue swelling.

Understanding Tensile Strength and Knot Security

Two physical properties define the reliability of a suture: tensile strength and knot security. Tensile strength refers to the amount of weight or pull the suture can withstand before it breaks. High tensile strength is crucial for holding together tissues that are under tension, such as an abdominal wall closure or a dynamic joint area. If the suture breaks, the wound opens, leading to complications. Polypropylene and polyester are known for maintaining their strength over time.

However, a strong suture is useless if the knot slips. Knot security is the ability of the suture material to hold a knot without it unraveling. Braided sutures generally offer excellent knot security because the braid provides friction. Monofilament sutures, being smooth, can be slippery and may have poor knot security if not tied with extra throws (loops). A surgeon must balance these factors. For example, nylon is strong but requires a careful technique to use to ensure the knot stays secure. If the knot fails, the closure fails.

Choosing the Right Needle and Thread for the Job

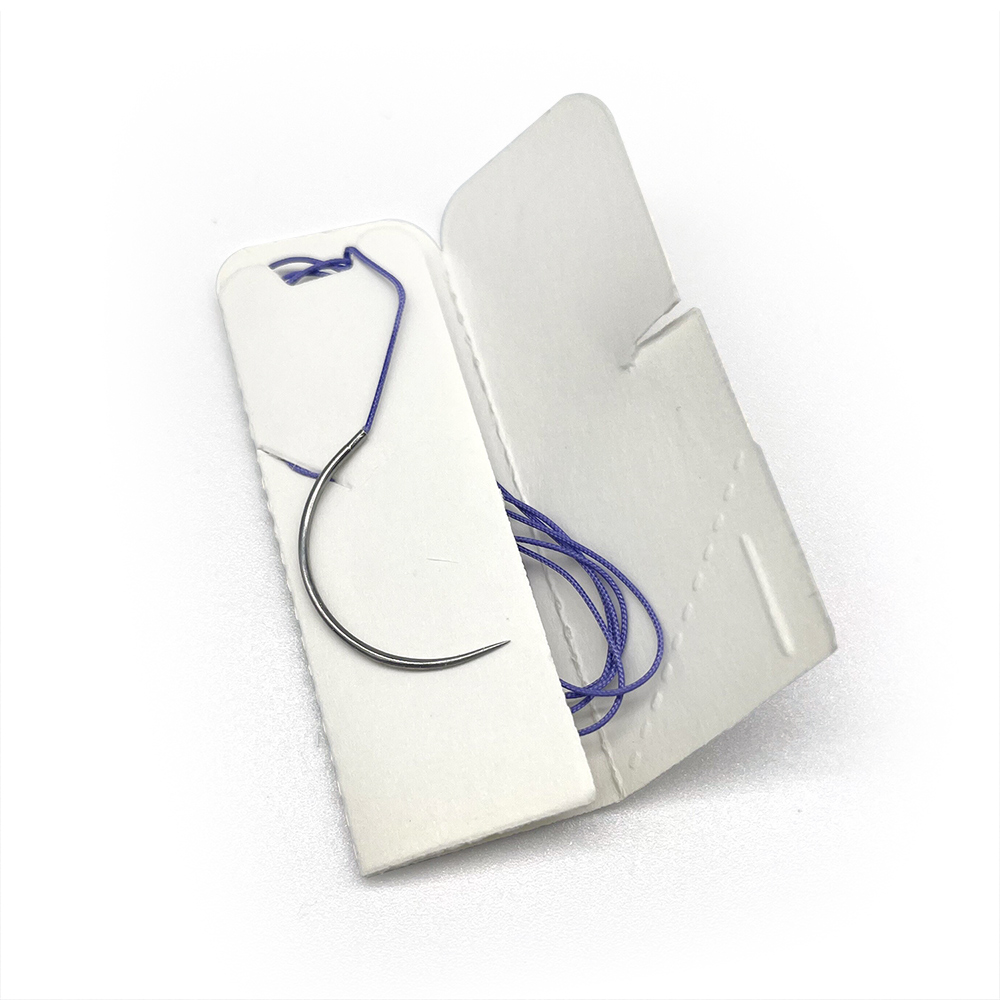

A suture is rarely used without a needle. In fact, in modern sterile suture with needle packaging, the suture is swaged (attached) directly to the needle. The needle must be chosen as carefully as the thread. Needles come in various shapes (curved or straight) and points (tapered for soft tissue, cutting for tough skin).

The diameter of the suture is also critical. Suture sizes are defined by U.S.P. (United States Pharmacopeia) standards, usually denoted by numbers like 2-0, 3-0, or 4-0. The larger the number before the zero, the thinner the suture. A 6-0 suture is extremely fine, used for cosmetic surgery on the face or ophthalmic procedures to minimize the scar. A 1-0 or 2-0 suture is thick and heavy, used for high-tension areas like the abdominal fascia. Using a thick suture on a delicate laceration would cause unnecessary trauma, while using a thin suture on a heavy muscle would lead to breakage. The needle and suture must work in harmony with the tissue.

Specific Applications: From Abdominal Closures to Cosmetic Repairs

Different medical scenarios demand different types of sutures. In cardiovascular surgery, polypropylene sutures are often the gold standard because they are non-thrombogenic (don’t cause clots) and last forever. For an abdominal surgery, where the fascia needs to hold against the pressure of breathing and movement, a strong, slowly absorbable loop or a permanent non-absorbable suture is required.

In cosmetic surgery, the goal is to leave little to no trace. Here, a fine monofilament like nylon or poliglecaprone is often used because it creates less tissue reaction and thus a smaller scar. For mucosal tissues, like inside the mouth, fast-absorbing gut or Vicryl is preferred so the patient doesn’t have to return for suture removal. Sutures are placed strategically based on the healing time of the specific tissue. A tendon takes months to heal, so it needs a long-lasting suture. Skin heals in days, so the suture can be removed quickly.

Mastering Suture Techniques: Continuous vs. Interrupted

The suture material is only half the equation; the suture techniques employed by the surgeon are the other half. There are different suture patterns. A continuous suture (running stitch) is quick to place and distributes tension evenly along the entire wound closure. It uses a single piece of suture material. However, if that one strand breaks at any point, the entire closure can come undone.

Alternatively, interrupted sutures consist of individual stitches, each tied with a separate knot. If one stitch breaks, the others remain intact, maintaining the closure. This technique takes longer but offers greater security. The technique to use depends on the length of the incision and the risk of infection. For example, in the presence of an abscess or infection, interrupted sutures are safer because they allow for drainage if necessary. The surgeon selects the technique that best suits the mechanical needs of the tissue and the safety of the patient.

The Crucial Process of Suture Removal

For non-absorbable sutures, the process ends with suture removal. Knowing when to remove stitches is an art. If left in too long, the suture can leave "railroad track" scars or become embedded in the tissue swelling. If removed too early, the wound might dehisc (open up).

Generally, sutures on the face are removed in 3-5 days to prevent scarring. Sutures on the scalp or trunk might stay in for 7-10 days, while those on limbs or joints might remain for 14 days. The process requires sterile scissors and forceps. The knot is lifted, the suture is cut close to the skin, and pulled through. It is vital to never pull the contaminated outside part of the suture through the clean inside of the wound. Proper suture removal ensures a clean, cosmetic finish to the surgical incisions.

Why Sourcing the Correct Suture Material Matters for Hospitals

For the buyers stocking the shelves, understanding various types of sutures is a matter of patient safety and budget efficiency. A hospital cannot function without a diverse inventory. You need catgut for the OBGYN ward, heavy nylon for the ER laceration repairs, and fine monofilament for plastic surgery.

Sutures are used in almost every medical department. Different types of sutures solve different problems. Using a braided suture on an infected wound could lead to complications, just as using a weak suture on a high-tension wound could cause a rupture. Whether it is natural and synthetic, or absorbable and non-absorbable sutures, quality consistency is key. We ensure that every suture we manufacture, from the needle sharpness to the tensile strength of the thread, meets rigorous standards. Because when a suture is placed, it has one job: to hold everything together until the body heals itself.

Key Takeaways

- Difference Defined: A suture is the material (thread); a stitch is the loop/technique made by the surgeon.

- Material Types: Monofilament sutures (like nylon) are smooth and reduce infection risk; braided sutures (like silk suture) offer better handling and knot security.

- Absorbability: Absorbable sutures (like catgut or Vicryl) dissolve and are used internally; non-absorbable sutures (like polypropylene) must be removed or provide permanent support.

- Tissue Reaction: Synthetic materials generally cause less tissue reaction and scarring compared to natural fibers.

- Strength: Tensile strength determines if the suture can hold the wound under tension; knot security ensures it stays tied.

- Sizing: Sizing follows U.S.P. standards; higher numbers (e.g., 6-0) mean thinner sutures for delicate work, while lower numbers (e.g., 1-0) are for heavy-duty closure.

Post time: Jan-16-2026